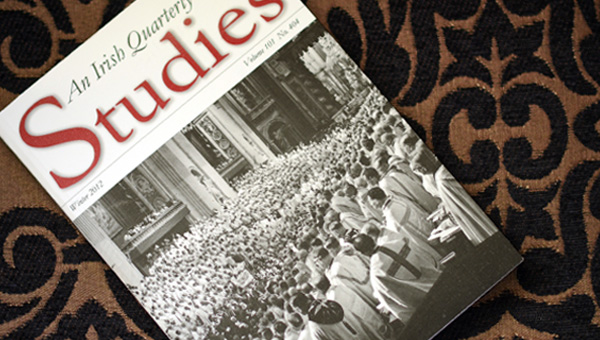

Coming to terms with Vatican II

“Fifty years on,” says Studies editor Bruce Bradley SJ in the latest issue, “we live in a church manifestly struggling to come to terms with its inheritance from Vatican II.” And many of the contributors note how the dramatic changes of the last fifty years have dissipated much of the hope and optimism which emerged after the Council ended in 1965.

There is, perhaps, a note of anxiety in some of the essay titles: Gerry O’Hanlon SJ writes of ‘Irish Catholicism at a crossroads’; Jim Corkery SJ asks ‘Whither Catholicism in Ireland?’; ‘How did it come to this?’ asks Brendan Hoban; and Breda O’Brien speaks of ‘Going beyond the divisions’. Most of these contributors note the “melancholy, long, withdrawing roar” of the sea of faith retreating during these past decades, but there is more than an occasional expression of hope. Gerry O’Hanlon notes how renowned canonist Ladislas Orsy SJ, in spite of his clear vision of how the Church has ungenerously reneged on its conciliar commitment to collegiality and structural reform, “remains hopeful, even buoyant, about our possibilities, because there is something irresistible about the tsunami of energy and love released by the Holy Spirit at the Second Vatican Council, and this is a wave that we, as faithful disciples of the Lord, are called to surf in our day”.

O’Hanlon also notes Orsy’s suggestion that “by a subtle divine law, they – the faithful of today – are the legitimate heirs of the Council”. A different angle on the same issue is provided by Declan Kiberd in his insightful – and amusing – essay on ‘Ireland after aggiornamento’. Not all change in the wake of the Council was good, he observes, recalling the folk masses that replaced the “soaring melodies” of the Latin Mass, “conducted by guitar-toting, three-chord clerics, many clad in Aran sweaters”. “Yet the new Catholicism was not superficial,” he remarks. “For one thing, the idea of a Mass sung in the vernacular licenced not only the throbbing intensity of the Missa Luba but also the beauty of the Ó Riada Mass, as sung by the choir at Cuil Aodh.”

“For another,” Kiberd adds, “the priest no longer faced forward at a high marble altar but turned instead at a low and humble table to confront what John McGahern called ‘the ultimate mystery: his own people’.”