Why Darwin’s theory cannot explain the human mind

Bill Toner :: [1] Darwin’s theory of evolution was an important scientific breakthrough, but it also had a big impact on religious belief. Before the publication of his The Origin of Species in 1859, most practicing Christians took literally the account in the Book of Genesis that God directly created all the kinds of wild animals on one particular day, – “the sixth day”. Darwin proposed instead, on the basis of his research and global exploration, that species of animals, and eventually humans, had generally evolved from earlier species, over millions of years. This new theory weakened the belief of many people in the creative action of God, since it seemed to contradict the biblical account of God directly creating every species of animal, and this in relatively recent times. Darwin went further and proposed also that life itself originated naturally in a “warm little pond” of inorganic matter, which seemed to render the creative work of God even more redundant.

The idea of ‘natural selection’ was central to Darwin’s theory. The process seems to work like this: in all living things small random variations occur and can be passed on from one generation to the next. If a variation confers an advantage it is likely to be ‘selected’ and passed on. One real example often given is that of a particular moth common in England. It was often eaten by birds. However some moths were lighter in colour than others and they blended in with the tree trunks on which they roosted and were not noticed by the birds. The birds then ate the darker-coloured moths, and the general colour of the species gradually remained light in colour. When the Industrial Revolution came the smoke from the furnaces blackened the trees. The lighter coloured moths now stood out and were eaten. The darker moths escaped and produced more offspring than the lighter ones so that in a few years the moths were predominantly dark in colour. When clean air acts were passed the process went into reverse. The trees became cleaner. The darker-coloured moths now became more visible and were eaten by birds and the lighter-coloured moths survived to produce more offspring.

Over millions of years of life on earth some very significant variations occurred in some species, due to genetic mutations. For instance some four- legged creatures developed malformations of the front limbs, – some kind of flattening – which allowed them to swim or even glide better than other members of the species. In this way they were able to exploit ‘niches’ in the natural world which gave them better access to food. Examples of these are bats and ‘flying foxes’ (Pteropus). In order to make use of the new ability to fly or glide, there needed to be some developments of the brains of these creatures. Brains that controlled the ability to walk were not necessarily able to control the ability to fly. The way brains develop to keep pace with new physical possibilities that are brought about by evolution is a bit of a mystery. In the late 18th century it was discovered that brains could change through growth and reorganization of neural pathways. This is known as plasticity of brains.

The important point in the present context is that (until the emergence of human beings) the growth and development of brains just kept pace with the new physical developments they needed to control. As new animal species developed, the key point for evolutionary purposes was that they would survive physically in order to produce offspring. For this they needed some imprinted instincts, mainly for sex, nurturing of young, and ability to find food. These animals had to have a limited degree of intelligence, for instance the ability to move a stone that was obstructing them when searching for food. However, the instincts and abilities provided by the evolutionary process were strictly those required to survive physically, and to reproduce. The brains of these animals developed just sufficiently for these purposes, but no further. Apart from humans, there is no evidence of ‘development’ in any animal species over generations, except for a limited amount of learning in such matters as finding new sources of food, which might be imitated by their offspring. The pet dog at the end of your lead is likely to have the same habits and capacities as a similar dog had in the middle ages. Species of animals have not, unlike humans, gradually madez inventions, and developed cultures.

When man emerged from the evolutionary process something very strange happened. The mental capacities of these humans seem to have been adequate for more than mere physical survival. Sometimes we see imaginative artistic reproductions of early humans. As often as not the artists (some of whom may be palaeontologists) will picture them sitting in groups around a fire, holding primitive spears, and often wrapped in animal furs. It can be argued that some of these things (fire, spears, furs) were necessary for physical survival. But they were not the direct result of the genetic mutations which produced the physical characteristics of the homo sapiens. And it has never been suggested that their genes contained lists of imprinted instructions on lighting fires, attaching suitable arrow heads to spears, or sewing lessons suited to animal furs. Rather, these items were a product of the brain capacities and abilities of the new species. These brains were being assisted by new powers of discovery, insight, abstract reasoning, decision-making, and self-consciousness (the experience of ‘I’).

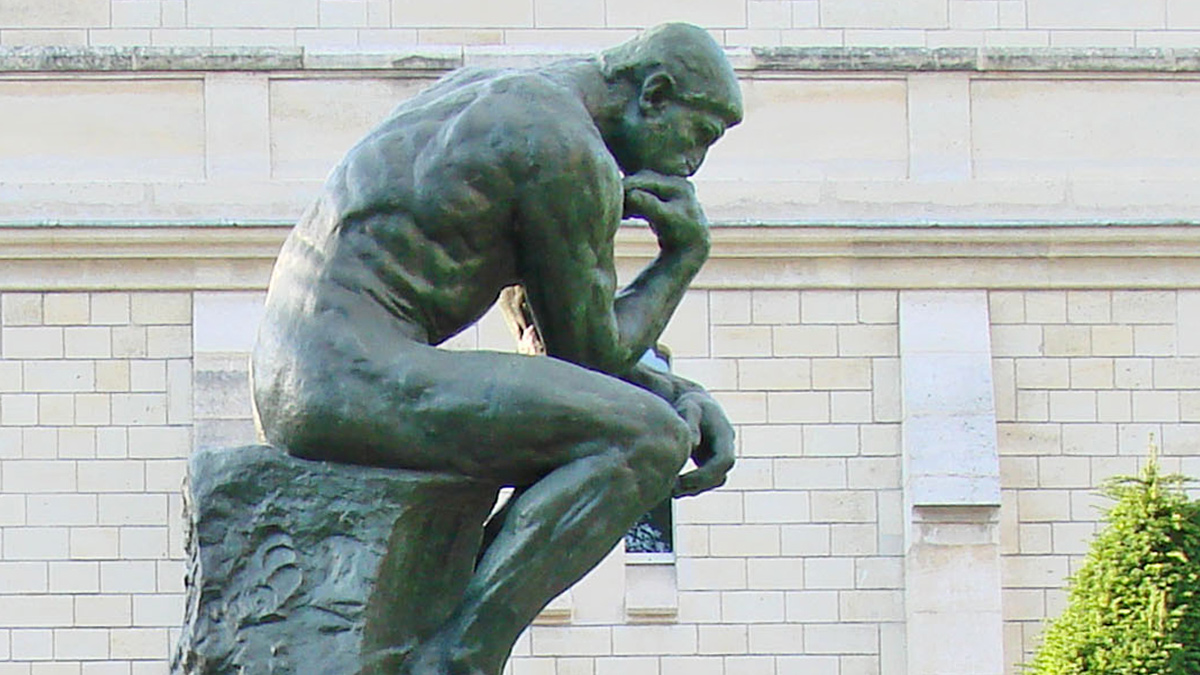

The brains of humans were indeed bigger that those of earlier animals, and it might be thought that this explained their ability reason and make discoveries. But it was gradually concluded by many early philosophers that the ability of humans to process abstract ideas could not depend solely on material properties, and the notion of ‘mind’ or ‘intellect’ came to be used to refer to the highest mental capacities of humans. The increase in size of their brains was indeed necessary, to contain the new brain cells and connections needed to process complex thought processes. But their new non-material powers could not be accounted for by their physical brains, of whatever size. Thomas Aquinas, following on from St. Augustine, saw the human mind or intellect as an immaterial power that allows humans to grasp universal truths (rather than just specific material things), to reason abstractly, and to make free choices. It was in this respect that they were seen as “made in God’s image”.

It follows that the human mind has many capacities which have nothing to do with survival of the fittest, in the sense that Darwin used term. Up to the emergence of man, it seems that evolution was parsimonious in the abilities it conferred on new species to survive. For instance, ground-nesting birds are very vulnerable to predators, especially new ones introduced by humans such as cats and dogs. Evolution simply did not confer on them sufficient adaptability or brain-power to recognize the dangers, and explore other survival strategies; nor has there been time for less vulnerable sub-species to emerge. Evolution only provided them with survival strategies which worked in the environment at the time of their emergence as a species. Many ground-nesting birds are now in danger of extinction, and may survive only through human intervention.

In comparison, human beings were endowed with a brain and additional powers and potentialities that had nothing to do with basic survival. However, they had shown immense powers of discovery and adaptation. Yet, the size of the human brain has not grown since its emergence in homo sapiens. Therefore we can assume that the brains of our cave-dwelling ancestors had the potential to handle the theorem of Pythagoras, differential calculus, set theory, logarithms, and the whole highly abstract world of mathematics. This knowledge has been crucial for the discovery and development of much of the theory of chemistry and physics, including quantum theory, relativity, probability, complex measurements used in astronomy, and so on. But as has been said, knowledge makes a slow and bloody entrance, so there was no possibility for our cave-dwelling ancestors to put techniques like differential calculus to use. Their first achievement was to surpass the ability of many wild animals to count up to three, and to develop a system of numbers. It took many centuries before the wonderful powers of the human brain could be realized in this particular field. Great thinkers carried on this development, – Pythagoras, Euclid, Archimedes, Newton, Gauss and Euler were particularly prominent.

An extraordinary by-product of the work of Pythagoras was his discovery of the mathematical basis of musical harmony. He discovered that when two strings of a certain length are plucked, they produce pleasing sounds if their lengths are in simple ratios such as 2:1 (an octave); or 3:2 or 4:3. He is sometimes said to be the founder of western music, but he also opened up an extraordinary vista of the mystery and wonder of the universe. It was a small example of the absence of boundaries in the human mind.

One thing that is clear is that it is very hard to see how the process of evolution, as expounded by Darwin and others, can explain the ability of the human mind to make discoveries of this kind. It is anathema to the Darwinian school to suggest that there is any teleology or ‘looking forward’ in the process of evolution. For instance, it would not be acceptable to this school to suggest that evolution, or nature, ‘knew’ that these abilities of the brain would come in useful some day. Contemporary evolutionary theory is totally focussed on the causes by which things arise, not on their purpose. In this view the cause of a physical change, such as a change in the shape of a limb, can only be a genetic variation. If this change is retained in the species, the only possible cause of the change remaining is because it turns out to be immediately useful to the survival of the new sub-species, and to its opportunity to procreate. To introduce the notion of purpose would invite the question, ‘Whose purpose?’, which might suggest the notion of some supernatural agent or ‘god’ into the equation, and this is unacceptable to modern Darwinian orthodoxy, which has ruled any mention of god as out of bounds in scientific research.

One theory sometimes proposed is that the human brain grew over the centuries in response to new challenges like quantum mechanics. However, there are two weaknesses in this theory. One is that the archaeological evidence indicates that the human brain has actually shrunk slightly since the emergence of homo sapiens. The other problem is that scientific discoveries have generally been made by individuals, not by the human race as a whole. It is not credible to maintain that a genetic variation that perhaps produced the brain of one ‘genius’ like Einstein somehow spread by natural selection through the whole human race to keep pace with scientific developments. It is sometimes forgotten that the basic mechanism of evolution (viz. that the individual of the species who is fittest for survival lives longer and so has more offspring to spread his successful genetic makeup) has broken down with the emergence of homo sapiens. In fact, historically, those best equipped to survive in society – the wealthier individuals – have tended to have fewer children than the poor. What has grown over the centuries is not the human brain, but the learning accumulated in the brain, especially by particular individuals.

Thomas Nagel, in Mind and Cosmos, identifies many aspects of our world that, in his view, cannot be explained by physical science. For Nagel, the human mind seems the most significant of these, as it was for Augustine and Aquinas. I have written here only about one mystery he deals with, which is how a species evolved with a brain loaded with capacities that played no part in its capacity to survive physically. In regard to this, Nagel states, “Is it credible that selection for fitness in the prehistoric past should have fixed capacities that are effective in theoretical pursuits that were unimaginable at the time?” (p.74).

However, Nagel devotes most attention to other properties of the mind that he does not see as having a purely physical explanation, even if they make use of the human brain. These are cognition (the ability to reason), consciousness, and the assignment of value. Nagel even raises major questions about the scientific efforts to explain the origins of life on earth: “No viable account…seems to be available of how a system as staggeringly functionally complex and information-rich as a self-reproducing cell, controlled by DNA, RNA, or some predecessor, could have arisen by chemical evolution alone from a dead environment”. Nagel is not religious and does not propose that the hand of God has been at work in the evolutionary process. Instead, he sees matter, and the entire cosmos, as having a purposive or teleological tendency. By this, Nagel means that in addition to the ordinary physical laws, teleological laws would assign higher probability to steps that have a higher “velocity” towards certain outcomes.

However, many of us will fall back on the insights of Augustine and Aquinas and their interpretations of the biblical text of Genesis 1:27, which state that man was made in the image of God. For Aquinas, the intellectual nature of humans is a key aspect of being created in God’s image. He sees the human intellect as a non-material or spiritual power that allows humans to grasp universal truths, to reason abstractly, and to make free choices. He did not believe that the intellect was a physical part of the body, but rather a power of the soul. For Aquinas the soul is the very essence of a living being, the principle that animates it and makes it alive. It too is clearly beyond the reach of contemporary human science.

[1] I am indebted to Thomas Nagel’s book, Mind and Cosmos, Oxford University Press 2012, for providing the main ideas for this blog, even if Professor Nagel would not agree completely with my conclusion. I am also indebted to Conall O’Cuinn for reading my previous blogs in this area and sending me on a trail of discovery to the work of Thomas Nagel, who is University Professor of Philosophy Emeritus at New York University.