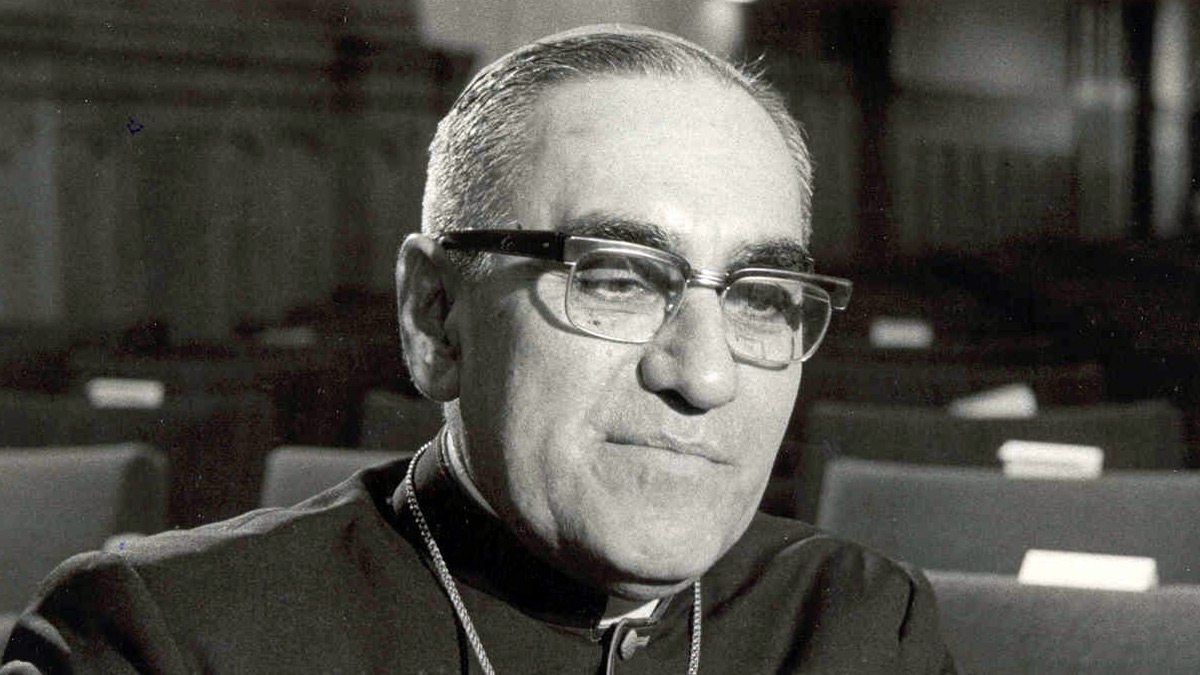

The greatness of Oscar Romero

Next Sunday, 14 October, Pope Francis will canonise Blessed Oscar Romero, the Salvadoran archbishop who was martyred on 24 March 1980. He was shot as he celebrated Mass, a reprisal for his opposition to the repressive oligarchic government and his defense of human rights.

It was during Romero’s three years as Bishop of Santiago de María, before he was appointed to the capital, San Salvador, that he came to see the extreme poverty and the brutal repression of ordinary Salvadoran campesinos, and he became convinced of the radical incompatibility of his country’s political and military structures and the tenets of the Catholic faith. What really galvanised him into concrete action, however, was the brutal assassination of his close friend and Jesuit priest, Rutilio Grande. This happened only a few weeks after Romero was installed as Archbishop of San Salvador in February 1977. His decisive and highly public opposition to the government from then on practically ensured his own eventual assassination.

Archbishop Romero was beatified on 23 May 2015 in the central plaza of San Salvador by a representative of Pope Francis.

Also due to be canonised on Sunday is Pope Paul VI, the pope who led the Church through the last years of Vatican II and the turbulent years which followed, up to his death in 1978. Five other people will be canonised at the same event in Rome: Father Francesco Spinelli of Italy, founder of the Sisters Adorers of the Blessed Sacrament; Father Vincenzo Romano, who worked with the poor of Naples, Italy, until his death in 1831; Mother Catherine Kasper, the German founder of the religious congregation, the Poor Handmaids of Jesus Christ; and Nazaria Ignacia March Mesa, the Spanish founder of the Congregation of the Missionary Crusaders of the Church.

Below we re-publish an article by Michael O’Sullivan SJ in Spirituality about the life, death and significance of soon-to-be-saint Oscar Romero.

—————-

Archbishop Oscar Romero, Martyr

Michael O’Sullivan SJ [1]

Published in Spirituality (March-April 2015) 21/119: 119-23

On 2 December 1980, Ita Forde, Maura Clarke, Jean Donovan, and Dorothy Kazel were coming from the airport in San Salvador, capital of El Salvador. Ita, Maura, and Jean had Irish ancestry and Jean had only recently returned to El Salvador after a year studying at UCC. Ita, Maura, and Dorothy were US religious sisters and Jean was a US lay missionary. Dorothy and Jean had gone to the airport to collect Ita and Maura, who were returning from a conference of the Maryknoll sisters in neighbouring Nicaragua. The deep Christian faith of the four women had led them to live and work among the economically poor of San Salvador.

But now their hour had come (see Mk 14:41). December 2nd was to be their last day in this life. They were kidnapped by 5 members of the El Salvador National Guard acting under orders, driven to a field where cattle graze, beaten, raped, and murdered. The previous night, at the liturgy to close the conference she and Maura were attending, Ita read this passage from one of Archbishop Romero’s last homilies:

Christ invites us not to fear persecution because, believe me, brothers and sisters, the one who is committed to the poor must share the same fate as the poor. And in El Salvador we know what the fate of the poor signifies: to disappear, to be tortured, to be held captive, and to be found dead by the side of the road.

The murder of these four women shows that in honouring Romero as a martyr we are also honouring by implication all the church workers and missionaries, whose faith inspired them to put their lives on the line for God and God’s dream of a better life for everyone in a country named after Jesus – El Salvador means ‘The Saviour’.

Romero as a symbolic martyr

As well as being a symbol of all the martyrs of El Salvador and Latin America in those years, Archbishop Oscar Romero is also a martyr of the Church of the Second Vatican Council, which had declared, “the joys and hopes, the grief and anguish of the people of our time, especially those who are poor or afflicted, are the joys and hopes, the grief and anguish of the followers of Christ” (GS1).[2] But Oscar is a martyr and symbol even more of the Church of Medellín and Puebla, the two great conferences of Catholic bishops of Latin America which took place in the light of the Council. The bishops at Medellín (1968) had said, “Latin America will undertake its vocation to liberation at the cost of whatever sacrifice” [3]; the Puebla conference (1979) declared explicitly that all Christians were called to a preferential option for the poor aimed at their integral liberation. [4]

Oscar Romero’s martyrdom is closely linked to that of his Jesuit priest friend, Rutilio Grande. On 12 March 1977, Grande drove from Aquilares to El Paisnal to say evening Mass. He was accompanied by an old man, Manuel, and a teenager, Nelson. A pick-up truck was following them. Ahead they saw a blue car with California plates. The pickup accelerated and came up menacingly right behind them. Rutilio and his companions were clearly in danger. One of the men by the side of the road lit a cigarette. This was the signal for murder. The bullets came from both sides as well as from behind. They went into Rutilio’s neck and head and into his lower back and pelvis. A further shot was fired. It killed Nelson who had suffered an epileptic seizure, but was, apparently, still alive. Grande was murdered because his faith had inspired him to become a great champion of the rural poor in his own land. Manuel and Nelson were assassinated because they were witnesses, nobodies for their killers, and in the way.

The three were brought to the church and if you go there today you will see three slabs on the ground, each with the name of one of the dead on it – the Jesuits wanted all three buried side by side. Three weeks earlier, a new Archbishop, Oscar Romero, had been appointed in El Salvador. He was not the choice of those who were engaged strongly in a faith-based struggle for justice. They saw him as being too timid to give the leadership they wanted, and needed. But he was a friend of Rutilio Grande – a large photo of Grande hung in his simple home when I went there in 1991. Eva Menjívar, a missionary sister who knew Romero and worked with Grande, was tending Rutilio’s corpse the night he was killed. She was “using a towel to absorb the blood that was trickling out, when Romero arrived. She said Romero approached the corpse and, after standing in silence for several moments, said, ‘If we don’t change now, we never will.’” [5] It now fell to the new Archbishop to lead the prayers for his friend and for his friend’s travelling companions who, being poor in economic terms, were among the vast majority of the people in the country. As well as praying for long periods that night beside the body of his friend and in the company of the poor peasants Romero stayed on for long hours listening to and talking with them and seeing the pain in their eyes. The whole experience led to what he called “a divine inspiration”: he had to stand up for these people, speak out on their behalf, and face down the violent repression against them. He felt his timidity fall away and in its place came great confidence, courage, and conviction. He had always felt a special closeness to the poor, but now after Grande’s death he felt it even more (Grande’s cause for beatification has now been opened).

His first public action was to cancel all the Masses in the diocese for the following Sunday and to hold one Mass in the cathedral. He ran into strong opposition from the apostolic nuncio, who was later the nuncio in Ireland, as well as from many of the bishops. However, 100,000 people came for the Mass and 150 priests concelebrated. Romero called for a full investigation into the killings of Grande and his travelling companions during the Mass and said he would not take part in any state functions until this had happened. It never happened and so he was conspicuously absent from such events thereafter.

Bonds with the Jesuits

While he and Grande were good friends, he also had a lot of appreciation for Jesuits. He had done his theology studies with the Jesuits in El Salvador and at the Jesuit University in Rome. He had also done the thirty day spiritual exercises of St Ignatius, which all Jesuits do at least twice in their lives, and Jesuits were his spiritual directors and confessors. After Grande’s death he became a good friend of Jon Sobrino, the renowned liberation theologian who opened the door to him when he arrived on the night of Grande’s murder and who became his theological advisor. Sobrino had escaped martyrdom in November 1989 when the six members of his Jesuit community were dragged from their beds and assassinated by an army death squad [6], along with Elba Julia and her daughter, Celina, who had taken refuge with the community because they feared for their lives after their home had been damaged by army gunfire. The murdered Jesuits included Amando Lopez who had done his theology studies at the Jesuit house of studies in Milltown Park, Dublin and was ordained in the chapel there, and Ignacio Ellacuría, the head of the University, who had completed his Jesuit training here in Dublin. [7] In a Mass in the university chapel for Romero after he was martyred, Ellacuría had said, “in Archbishop Romero, God has passed through El Salvador.” Those responsible for the killing of Romero, Grande, Ellacuría and companions, the mother and daughter, and the four US women missionaries had all been trained at the School of the Americas in Fort Benning, Georgia, USA. [8]

Running risks for God

While Grande’s death had a very big say in bringing about the change in Romero it also has to be kept in mind that Romero’s family led a life of poverty and austerity. Like Jesus, he also worked as a carpenter for a time. Like Jesus he lived a life of profound intimacy with God. Like Jesus his faith inspired him to make a radical option for the poor which meant he proclaimed the gospel in a way that resulted in him being killed like Jesus, after just three years as Archbishop.

Prior to his death he had received countless death threats, but he made it clear that “he would not abandon his people”. He reflected often on martyrdom as his priests and very many of his catechists were killed, and he assisted at their funerals.

He sometimes said, “A Church which does not suffer persecution, but in fact enjoys the privileges and the support of the world, is a Church which should be afraid, because it is not the true Church of Jesus Christ.” On 24 July 1979 he said: “It would be sad that in a country in which there are so many horrible assassinations there were no priests counted among the victims.”

The day before he was killed he appealed publicly to the soldiers urging them to cease the repression and lay down their arms. “After that appeal he seemed at peace”. He went for lunch with a family who were friends of his and played with the children. But during the meal he experienced a moment where “he wept openly”. “He remembered his best friends and spoke about the gifts God had given each of them”. [9] He knew his hour was near.

His hour had come

On 24 March 1980 he was celebrating Mass in the chapel of a cancer hospital. The chapel was very near the simple home where he lived. At 6.25 pm local time, a lone gun man entered the chapel and killed the Archbishop with a single shot during the offertory of the Mass. He fell to the ground, and his blood oozed out at the feet of the crucified Jesus hanging on the cross just above him behind the altar. The killer was a professional hit man carrying out a contract killing. It was the eve of Holy Week when the Church worldwide commemorates the mystery of its own life, and in a small and economically poor country we had heard proclaimed anew the words of John’s Gospel: ‘A man can have no greater love than to lay down his life for his friends’ (John 15:13).

Romero saw the struggle for justice in his country as a struggle against forces that were not simply political and economic, but demonic. He saw it as a struggle against the forces of sin. He knew such forces had killed Jesus, but he also believed in the resurrection of Jesus against these forces that appeared initially to have overcome and done away with him. And because Romero believed in this Jesus, three weeks before he died he said: “If they kill me, I will rise again in the Salvadoran people. My voice will disappear but my word, which is Christ’s, will remain. I say this without pride, with great humility.” [10] He also said: “I hope they will realize they are wasting their time. One bishop may die, but God’s Church, which is the people, will never die.” “May my death be for the liberation of my people”.

May the martyrdom of Oscar Romero inspire us to deepen our intimacy with God and to commit ourselves even more firmly to God’s dream of a world of beauty, truth, goodness, and love! Amen! Alleluia!

———–

1. This is the text of Fr. O’Sullivan’s homily at the Mass to honour the announcement of Oscar Romero as a martyr. The Mass was held at St. Francis Xavier Church, Upper Gardiner St., on 15 Feb 2015. Fr. O’Sullivan is the Director of the MA in Christian Spirituality, and Cluster leader of PhD and MA by research spirituality students at All Hallows College, Dublin City University. He is a Research Fellow at the University of the Free State, South Africa.

2. Gaudium et Spes, in Vatican Council II: Constitutions, Decrees, Declarations, edited by Austin Flannery (Dublin: Dominican Publications, 1996 (2007 printing), n. 1.

3. Second General Conference of Latin American Bishops, The Church in the Present-Day Transformation of Latin America in the Light of the Council: Conclusions (Washington, D. C.: Secretariat for Latin America, National Conference of Catholic Bishops, 1979, 3rd ed.), 23.

4. Third General Conference of Latin American Bishops, Puebla: Evangelization at Present and in the Future of Latin America: Conclusions (Slough: St. Paul Publications and London: CIIR, 1980, n. 1134.

5. Gene Palumbo, ‘The people in the parish have been waiting and waiting for this,’ NCR, 5 February 2015. http://ncronline.org/news/people/people-parish-have-been-waiting-and-waiting

6. He was out of the country at the time.

7. The other 4 Jesuits were Martín Baro, Joaquin Lopez y Lopez, Segundo Montes, and Juan Ramon Moreno,

8. Scott Wright, Oscar Romero and the Communion of the Saints (NY: Maryknoll, Orbis, 2009), 156, n.23.

9. See http://ncronline.org/news/people/people-parish-have-been-waiting-and-waiting

10. See Jon Sobrino, Witnesses to the Kingdom (New York: Maryknoll, Orbs, 2003), 180.