Studies: Ireland and euthanasia

In October 2020, People Before Profit/Solidarity politician Gino Kenny proposed a ‘Dying with Dignity’ Bill in Ireland’s parliament, the Dáil, which if enacted would allow people with terminal illnesses to end their lives. The Dáil voted to allow the Bill to move to the committee stage, during which it is closely scrutinised and amendments may be proposed.

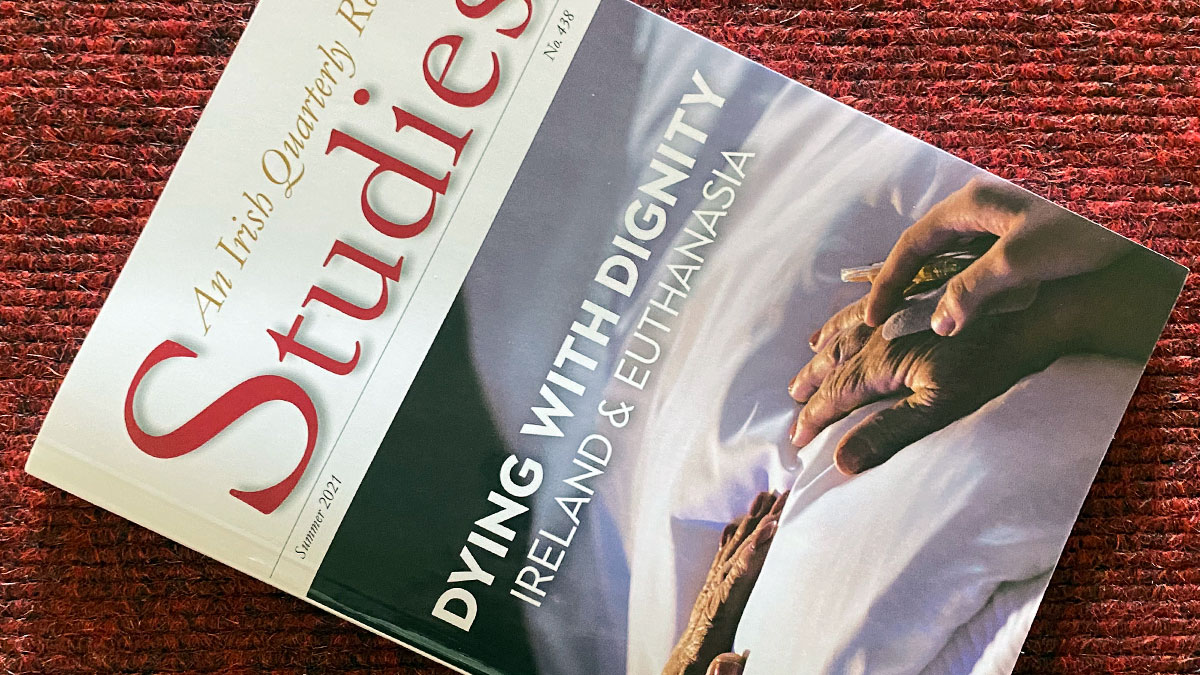

The Summer 2021 issue of Studies, the Irish Jesuit quarterly review, contains three substantial contributions to the broader task of public scrutiny. As editor Bruce Bradley SJ notes in his introduction, Gino Kenny called for “respectful, rational and meaningful debate” on the subject, and that is what Studies aims to provide.

The first is by Dr Noreen O’Carroll, lecturer in medical ethics at Royal College of Surgeons, Ireland. Her remarks in Studies are adapted from the submission she was invited to make to the Oireachtas Joint Committee on Justice in January. Dr O’Carroll identifies two spurious assumptions behind the bill, namely that the end-of-life loss of physical and cognitive abilities amounts to a loss of dignity and that death by assisted suicide or euthanasia is “flawless, painless and quick”. She then gives over a good part of her argument to identifying the euphemistic language of the bill which conceals the less romantic realities of the practice it proposes. She is particularly concerned that the attitude the bill endorses would compromise the proper clinical management of patients’ illness:

Good end-of-life care includes not only specialised clinical programmes to control physical pain but also counselling and human support to minimise psychological pain and soul pain; family and community support groups to counter social pain; and pastoral care to address spiritual pain. Putting sufficient resources in place to ensure that good end-of-life care is available to people everywhere would be of far more worth and practical use to patients and families in Ireland than passing the Dying with Dignity Bill 2020.

Dr O’Carroll also identifies some of the ways in which the bill could adversely affect communities and society at large. These include that: it violates the boundary of the ethical practice of medicine; it destroys the fiduciary nature of the doctor-patient relationship; it normalises suicide and jeopardises the suicidal; and it undermines a key principle of palliative care, namely that it intends neither to hasten nor to postpone death. In summary, she sees the current move to legislate in this area as a strike against a culture of life which is in need of renewal in Ireland and throughout the world.

Dr Gerry O’Hanlon SJ takes a very different tack in his essay on ‘Human suffering and human dignity’. His concern is with reflecting theologically on the common human experience of human suffering and dignity so as to reach a deeper understanding of the issues at the base of the current move to legalise euthanasia and assisted suicide. He readily acknowledges that we find it hard to understand how conditions such as radical dependence on others, the loss of control over bodily functions, organ failure, and the onset of depression can be compatible with human dignity, but he urges the reader to dig a bit deeper. He poses a question: “What if pain and suffering, even involuntary, have meaning and value and can be considered compatible with human dignity?”

In particular, Dr O’Hanlon focuses attention on the redemptive role of human suffering disclosed especially in the life and death of Jesus Christ. What Christ models is God’s own method of repairing the brokenness of the world precisely through self-emptying, including death on the cross: “This ’emptying’ is revealed as a profound act of love and touches into that basic instinct which recognises that, in the context of sin and evil, love is costly, love involves suffering.” Christ’s suffering is a response to the laments of the people of God.

The understanding here, then, is that the world is manifestly in need of repair. The freedom which is so important to us can produce much good, but it also leads to harm, evil, and social and personal sin.

The consequent harm to individuals and communities is unimaginable: we experience some of this in our personal lives (our broken relationships, our failed projects, our personal dissatisfactions and regrets with life) and witness it dramatically in the lives of others – the poor, prisoners, migrants, minorities of all kinds, our wounded planet. And we intuit how this virus of sin goes beyond individuals and even communities to enter into the very fabric of society itself – its culture, structure and institutions.

This is the world that needs to be repaired. In this context, suffering has a critical role to play. The suffering which comes from striving to right the wrongs of the world or to heal and restore the broken lives of families, friends and communities – just as Christ’s suffering did – has an obvious value and in no way reduces the dignity or value of the sufferer. But even simply sharing in that suffering of Christ on the cross, gaining solidarity with all those who suffer involuntarily around the world, has an immense restorative value.

Dr O’Hanlon does not try to address the political question posed by Gino Kenny’s bill. His essay is “an attempt to expand our horizons, so that we might catch a glimpse of something important which our dominant culture occludes,” namely the value of human suffering. This may invite us, he says, “into a different existential space when we reflect on our own mortality”.

In the third essay on the subject of assisted dying, Dr Vincent Twomey echoes Dr O’Carroll’s concern that Kenny’s bill is lade with euphemisms which distract from the reality of what is proposed. By seeing the action as suicide, he notes, we see that the bill sends a strong signal of approval for an action that so many important initiatives in the country are working so hard against. Darkness into Light, for example, as well as other suicide prevention agencies aim to persuade men and women of all age groups “not to take what suicide has to offer”, but to find meaning and value where they may not be apparent to the patient. Facilitating assisted suicide also undermines, Dr Twomey argues, “the enormous strides in palliative care for the dying, which care truly enables the terminally ill to die with authentic respect for their real dignity… while they are surrounded by all the love and affection that their family, close friends, and understanding health care workers can offer”.

Also in this issue of Studies are: Mary Kenny on Gay Byrne as “the ‘conservative Catholic’ who changed Ireland”l; Greg Daly’s review of Are you there, God? It’s me, Ellen, the surprising and complex memoir of the pro-choice journalist Ellen Coyne; the second part of Brendan Walsh’s oral history of the contribution of the teaching Religious in Ireland; and the second part of David Ford’s incisive analysis of The Five Quintets, the magnum opus of Micheál Ó Siadhail.