‘I am baptised’ – words of hope at seminar

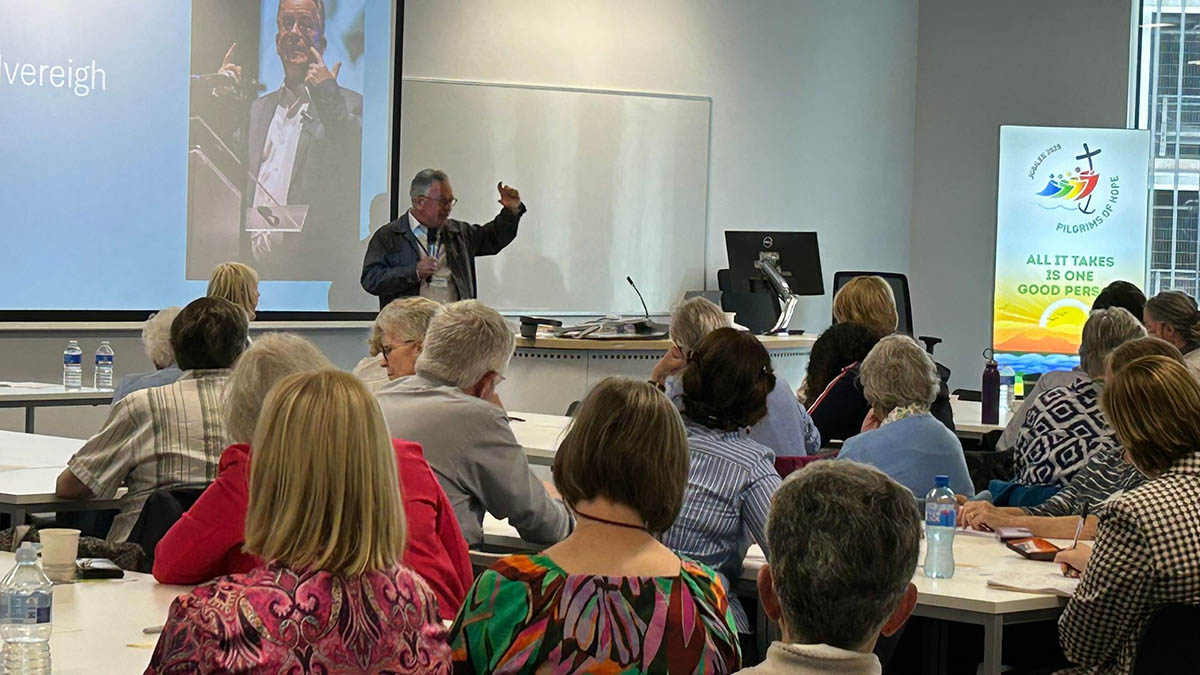

Julieann Moran’, General Secretary of the Irish Synodal Pathway, Bishop Alan McGuckian SJ of Down and Conor, and Austen Ivereigh, author and Synod ‘expert’ participant, were the guest speakers at the ‘On Being Pilgrims of Hope’ seminar organised by the Belfast Jesuit Centre on Saturday, 31 May 2025, The event was chaired by Pat Coyle, Director of Irish Jesuit Communications and over 120 participants attended.

After a warm welcome to all from the center’s director Gerry Clarke SJ the three speakers in turn addressed those gathered for 30 mins. The participants were then invited to model (in a modified version due to time constraints) the spiritual conversation method used during the the synodal processes that were part of “the largest global consultation process in the history of the world.” (Austen Ivereigh).

They were asked to reflect in silence on what they had heard before sharing with their table of six what had struck them or moved them. This first round of sharing was conducted without cross-talk, and followed by a second round within each group where people shared on what had stayed with them from the first round of sharing. An elected spokesperson in each group later fed back the fruits of their deliberation in a plenary session which was followed by a Q&A with the three speakers.

Julieann Moran was part of the leadership group that enabled Catholics in parishes all over Ireland to take part in the initial phases of Pope Francis’ synodal process of dialogue, discernment and sharing as a roadmap for development and reform within the church.

She spoke firstly about the Christian understanding of hope which she said was not a worldly optimistic disposition but rather a virtue “anchored in Christ’s resurrection” and active in our lives today. She said it was a virtue that calls us to “serve the poor and excluded; to build communities of welcome; to seek justice, mercy and peace.”

Outlining what is meant by synodality, she said it was a “walking together of all the people of God – clergy, laity and religious. It is the church, as the people of God listening, praying and discerning God’s will together, believing that the Holy Spirit is heard in every voice.”

She explained how the key messages from the Irish Synodal Pathway included a longing for inclusion and belonging because those who feel at home in the Church feel the absence of those who don’t. A deep desire for healing from past wounds was another message, as was the call for more co-responsible leadership and shared decision making, especially for women. And the need for faith formation and better adult catechesis was also voiced strongly.

Julieann truly struck a chord (as evidenced in group feedback) when she spoke about the importance of the sacrament of baptism, conferring on all the baptised the powers of the priest, prophet and king. She encouraged those present not to say ‘I was baptised’, but I am baptised.

Bishop Alan McGuckian SJ focussed his address on the final reflections of Pope Francis expressed in his last encyclical Dilexit Nos (He Loved Us) ». He quoted a number of passages from the document explaining how they were ‘powerful messages’ about the human and divine love of the Sacred Heart of Jesus Christ.

Pope Francis had used the term ‘polycrisis’ to describe the huge and often unprecedented challenges facing the world today, he explained. These include war, climate change, energy problems, epidemics, migration, and technological innovation. “All crises are a failure of the heart … and we must be people of the heart who co-exist with other hearts.” He encouraged those present to resist the temptation to say ‘our world is losing its heart’ but rather to believe in the power of the loving heart of Christ to mend wounded hearts, and a wounded earth. “We need to make reparation – which Pope Francis describes as a healing of relationships with our brothers and sisters and all of creation.” We do this by rooting our own hearts in the loving heart of God.

Austen Ivereigh is an author, journalist and broadcaster who was familiar to many who had seen and heard him commentating on the death of Pope Francis and the election of Pope Leo. He wrote the best-selling biographies The Great Reformer: Francis and the Making of a Radical Pope » and Wounded Shepherd: Francis and His Struggle to Convert the Catholic Church ». He also co-authored with Pope Francis Let Us Dream: The Path to a Better Future » He has been deeply involved in the Synod on Synodality, contributing, in various roles, to its differing stages.

He had all those present laughing when he told a story from his time in Rome covering the election of Pope Leo XIV. Toward the end of the conclave Austen had been ‘reading the signs of the times’ as it were, and strongly suspected that Cardinal Prevost (now the Pope) would be chosen by his fellow cardinals. Australian news was interviewing him and the camera operator had a shot of a baby seagull emerging from its egg just as white smoke emerged from the Vatican chimney. “What do you think that means?” he was asked, only to reply, “I think it means that chick knows we are all in for a surprise.”

After that he went on to share with those present what he had learnt from Pope Francis about hope. He noted how Francis had believed we were in an time of epochal change and crisis. He said that there were two responses to this that Francis decried. One was a naïve optimism that excluded God and personal freedom, believing rather that inexorable, impersona, historical forces would see to it all would be well. The other was a type of apocalyptic pessimism, a conviction that we are all doomed and the only possible response is an entrenched withdrawal from the world, a retreat into a beleaguered traditionalism.

Against this however, Francis saw the cross as the absolute sign of contradiction that reveals to humankind the reality of God’s grace and God’s merciful heart, working in history. Mercy bursts forth in a context that seemed impossible. The incarnated Christ becomes the risen Christ. Suffering, death, and resurrection is the wave pattern of human life, and it is in that direction that the arc of history bends. God’s power, discerned in prayer, silence and contemplation, is the only true power, and it calls to us to be bold, and creative in the face of the ‘polycrisis’.

Taking Artificial Intelligence as an example of a potential challenge or crisis Austen explained how we can view it as an impersonal technological force over which we have no control, “a fading of human faces into the fodder of algorithms.” But Christian hope, as explained by Francis, calls on us to resist such pessimism and claim our own agency. We are called to see, judge, act, or as Francis would have it, contemplate (free ourselves from filters that naively blot out pain or suffering), discern ( between what is God’s action – grace, and what is distracting us from that grace), and respond (take appropriate action).

An important part of this three-fold process in a time of crisis, according to Austen, is “the rediscovery of the virtue of ‘patience’ which is a distinctive hallmark of Christianity. The crises we face will not be solved instantly but ‘patientia’ is a knowing how to suffer well. It is the daughter of hope.”

The feedback from the ‘spiritual conversations’ conducted after the talks was rich and hopeful. People wanted to know how to engage further in synodal activities in their parish, how to create avenues to reach out to youth or for the excluded to return, and above all how to never forget the power of baptism bestowed on all the people of God – ‘I am baptised!’