Thomas of the Wounds and our vocation

Poor Thomas! Because he insisted on seeing the Risen Christ for himself, instead of taking the word of his fellow apostles that Jesus was alive, this apostle has become known as Doubting Thomas. We treat other apostles much better: Peter, even though he denied the Lord three times, is not referred to as “Denying Peter”. And although Jesus himself called James and his brother John “Sons of Thunder” (in the Gospel of Mark, Chapter 3), they never got stuck with the titles “Thundering James” or “Thundering John”. In comparison, Thomas has received a raw deal, being forever associated with doubt, as though he never got beyond it. Yet when he actually saw the Risen Christ, Thomas made one of the simplest and most radiant confessions of faith ever made, “My Lord and my God”. His faith was so strong that, according to tradition, Thomas travelled to India in 52 A.D., spreading the Good News there. When Saint Francis Xavier, the great Jesuit missionary, arrived in India 1,500 years later, he spent several months in the town of Mylapore near Chennai (Madras), where the remains of Saint Thomas are still venerated today, to honour Thomas and to ask for his help.

The famous story of Thomas’ refusal to believe that the Risen Jesus appeared to the other ten apostles is found in chapter twenty of Saint John’s Gospel. When the others tell Thomas they have seen the Lord, he responds, “Unless I see the marks of the nails in his hands and put my fingers where the nails were, and put my hand into his side, I refuse to believe.” A week later, Jesus appears to the apostles again, and this time Thomas is present. Jesus says to Thomas, “Put your finger here, see my hands. Reach out your hand and put it into my side. Doubt no longer, but believe.”

I’d like to propose re-naming this apostle “Thomas of the Wounds” instead of “Doubting Thomas”. I realize this sounds brazen: who am I to overturn centuries of tradition? I’d need some good reasons to do that. Well, that’s precisely what I’m going to provide: two good reasons. The first reason to change his name to Thomas of the Wounds is because this story about Thomas highlights something really important: Jesus’ wounds remain even after his Resurrection. The second reason: since the wounds of Jesus become glorious wounds, this can help us to see that even if our wounds don’t go away, they can nonetheless become a source of hope instead of dragging us back into the pain of the past.

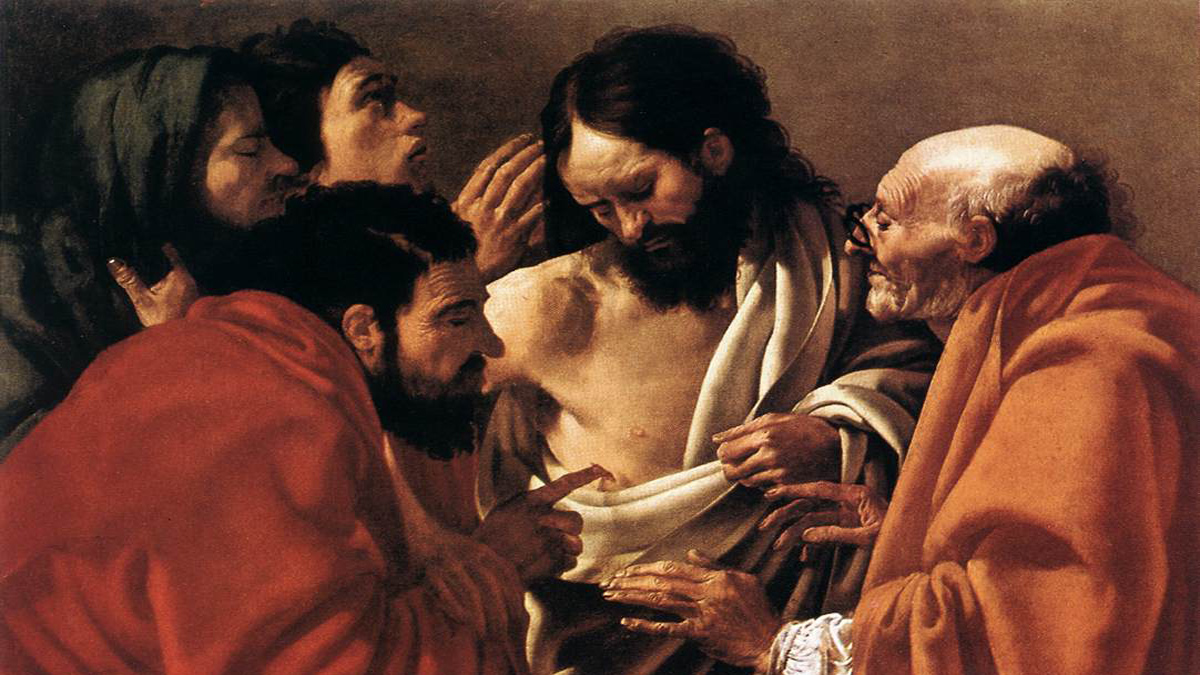

Now, I’ll say a little more about each reason. So much attention has traditionally been focused on Thomas’ doubt that most of us rarely reflect upon the fact that it is the wounds of Jesus that Thomas wants to see and touch. The episode with Thomas makes us acutely aware that Jesus’ wounds are still there, and even gives us a sense of how large and deep these wounds are. The wounds the nails make in the hands of Jesus are large enough for Thomas to put his finger into them. As for the wound in Jesus’ side, this gash made by the soldier’s lance is so big that Thomas can put his hand into it. When Jesus appears to Thomas and the other ten apostles, he tells Thomas to put his finger into the wounds in his hands and his hand into the wound in his side. But does Thomas actually touch Jesus’ wounds? The famous artist Caravaggio shows Thomas carefully inserting his index finger into the wound on Jesus’ side. The famous Scripture scholar Raymond Brown believes Thomas doesn’t touch Jesus at all, because nowhere does the text actually say that Thomas touches Jesus’ wounds. I tend to side with the artist rather than the scholar. Admittedly, the opinion of Raymond Brown has a lot going for it: not just the fact that the passage never says Thomas touches the wounds of his Master (though neither does it say that Thomas doesn’t touch the wounds of Jesus!), but also the fact that it makes sense that Thomas himself would be so overwhelmed in the presence of the Risen Christ that he would never dare to reach out and touch him. However, there is something in Caravaggio’s painting “The Incredulity of Saint Thomas” that moves me toward the opposite view. There I notice that it is Jesus who holds the right forearm of Thomas, guiding the apostle’s hand toward his side. It makes a lot of sense that Thomas is so overawed that he touches Jesus’ wounds only because Jesus himself gently but firmly gives Thomas (literally) a helping hand. Though at the same time what doesn’t ring true for me in Caravaggio’s painting is the scepticism I detect on Thomas’ face; Thomas would no longer have been doubtful at this point, but instead full of awe at being in the presence of the Risen Lord.

Whatever our vocation, whatever the path we take in life, we realize that some scars are so deep they never go away. And even though Jesus is truly risen, his wounds have not magically vanished. The fact that Jesus still bears his wounds after the Resurrection is a tremendous beacon of hope for the rest of us. On the face of it, woundedness is not something that inspires hope. We live in a culture that exalts perfectly shaped bodies and perfectly integrated personalities, and part of me wishes that someday I could get beyond my inner and outer wounds. I instinctively picture heaven as a state in which there’ll be no more scars. But this appearance of Jesus to Thomas and the other apostles suggests to me that I’ll always carry my brokenness, or at least the signs of my brokenness, with me. After all, Jesus is more perfect that I could ever be, yet he still has these visible and deep wounds in his Risen body. Jesus invites Thomas to place his fingers and hands in his wounds. Thomas won’t hurt Jesus by doing so, because these wounds, although still present, have now been transformed into glorious wounds. Even though my wounds won’t go away, with Jesus’ healing help, they will no longer fester and hurt me. My wounds don’t have to discourage me. They can become sources of light instead of being only reminders of pain. The apostles find great peace and joy in seeing the Risen yet still wounded Jesus. That’s reassuring: even though I continue to see my brokenness, I can be at peace, I can rejoice. In fact, my very woundedness makes me more like Jesus than having it all together ever would.

So, thanks to the apostle Thomas I have come to notice that the wounds of Jesus remain even after the Resurrection, and that these wounds show he has emerged victorious from an extraordinary battle against evil and death, and that someday, please God, I will be happy to display the scars that life inflicts upon me as a result of my less spectacular struggles.

I have good reasons to be grateful to this great apostle, who, according to tradition, was martyred by being pierced with a lance. To die in this way seems particularly appropriate for a saint whom I like to call Thomas of the Wounds.

Tom Casey is an Irish Jesuit priest and Dean of the Faculty of Philosophy at the Pontifical University in Maynooth.

Tom Casey is an Irish Jesuit priest and Dean of the Faculty of Philosophy at the Pontifical University in Maynooth.